how happy . . . that the livliest enjoyment is wholly independent on time place and situation–that the human mind is made for effort and there it is destined to find it’s honor and peace.

—Mary Moody Emerson to Ruth Haskins Emerson, 28 February 1813

From Henry Thoreau to Henry James and Virginia Woolf, transatlantic authors and literary critics have long recognized the accomplishments of Mary Moody Emerson (1774-1863), whether in her capacity as mentor to her famous nephew, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), or in her own intellectual right. As a single woman, Emerson refused proposals of marriage and relished the rare female privilege of property rights at “Elm Vale,” her home in Waterford, Maine. There, in seeming anticipation of Virginia Woolf’s prescription for a successful woman writer, Emerson enjoyed financial independence and a “room of her own.” In that enriching space for nearly fifty years, she assembled a voluminous series of manuscripts that she regarded as her intellectual and artistic legacy. She named them her “Almanacks” (c. 1804-1858).

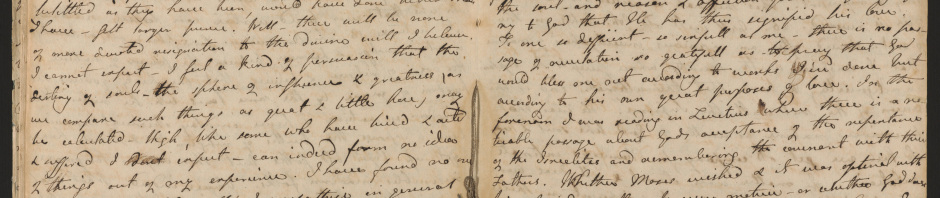

Constructed from letter paper and bound with thread, the Almanacks are hand-made booklets or “fascicles” running to over one thousand pages, and they display multiple genres, including letters, commonplace books, spiritual diaries, and original compositions; their content, however, largely consists of commonplace book quotations from and commentary on her extensive reading. Although Emerson published essays during her lifetime, these miscellaneous fascicles represent her most experimental expressions as a writer, an assessment amply confirmed by the ways in which the Emerson family used and preserved them and by their creative affinity with the writings of women such as the eighteenth-century British novelist Fanny Burney and nineteenth-century American poet Emily Dickinson, who are also indebted to the generic flexibility of the commonplace book.

The Almanacks’ subjects range from theology, philosophy, literary criticism, and science, to war, imperialism, and slavery. As such, this series of manuscripts provides a rare and prolific example of early modern women’s scholarly production as well as of a self-educated single American woman’s life during the antebellum era. In collaboration with the Women Writers Project (WWP), editors Noelle A. Baker and Sandra Harbert Petrulionis are at work on The Almanacks of Mary Moody Emerson: A Scholarly Digital Edition, a scholarly, annotated digital text of the complete Almanacks, published by WWP in its full-text selection of early modern women’s writing in English, Women Writers Online (http://www.wwp.northeastern.edu/wwo/). To date, twenty of the forty-seven total Almanacks have been published.

Emerson’s Almanacks contribute significantly to women’s intellectual history; document the extent to which early American women embraced transatlantic culture; and evidence the ways in which Emerson anticipates signal aspects of Transcendentalism, the antebellum movement for which her nephew is considered the primary spokesman. Our edition demonstrates that in adopting self-development as a conduct of life, Mary Moody Emerson serves as one of the earliest illustrations of an emerging critical reconsideration of Transcendentalism, envisaged through women. (See, for instance, a special double-issue of ESQ devoted exclusively to this subject: “Exaltadas: A Female Genealogy of Transcendentalism,” ESQ 57.1-2.) Highlighting the manuscripts’ material culture, the edition demonstrates Emerson’s ongoing engagement in manuscript circulation, generic experimentation, social authorship, and self-cultivation, attributes that anticipate the similar but more radical experiments of Emily Dickinson; it also provides specific examples of the modes of intellectual transmission between Mary and Waldo Emerson.